Rheanna Laderoute, from Ontario, died from an infection following a medical abortion.

When the 19-year-old learned she was pregnant, she didn’t tell her family. She drove to a women’s health clinic in Brampton, an hour away, where doctors prescribed her the abortion pill.

Two weeks after taking the pill, however, she was still bleeding heavily. She also experienced severe abdominal pain, which led her to the emergency room.

She arrived at the emergency department at Newmarket’s Southlake Regional Health Centre on February 14, 2022.

Less than two weeks later, she died of an infection that showed signs of septic shock.

In the days leading up to her death, Laderoute went to the emergency room three times. Despite the worsening of her condition, doctors failed to recognize the severity of her symptoms.

During her final visit, nurses were pleading for her to be transferred to the ICU, but it didn’t happen soon enough.

Following her death, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario launched two investigations into her case, which revealed that doctors had missed several red flags.

The necessary treatments and tests also weren’t provided in a timely manner.

One of the physicians who saw Laderoute, Marko Duic, had been warned by the college previously for inappropriate care and poor documentation. Despite being the subject of an investigation in 2018, however, he continued to see patients.

Refused ICU Care

The first time Laderoute visited the emergency room, the doctor who saw her ordered an ultrasound. The imaging revealed that she did not have any retained pacental or fetal remnants, which are common causes of infection following abortion.

The doctor referred her to an early pregnany loss clinic for more testing and discharged her.

The following day, the clinic was not able to get in touch with Laderoute to set up an appointment.

The following week, Laderoute returned to the emergency room, this time by ambulance. She had told emergency workers that her abdominal pain had gotten significantly worse.

She also complained of foul-smelling discharge, which required the use of 2-3 pads per day.

The doctor who saw her on her second visit to the ER was Dr. Duic. He diagnosed her with a peritonitic abdomen, which can be life-threatening.

He ordered bloodwork, imaging, and a urine sample. However, the college later determined that these tests weren’t sufficient to investigate her symptoms.

After being given pain and anti-nausea medications, Laderoute was able to walk. She was subsequently discharged, with a prescription for oral antibiotics as the doctor suspected she may have a urinary tract infection.

Just 24 hours after her discharge, Laderoute was brought back to the emergency room by ambulance.

Her heart rate had soared to 175 beats minute and her systolic blood pressure had dropped to 99. She also told the nurse that she had vomitted blood.

By 1 a.m., her systolic blood pressure had fallen to 84, and she was breathing rapidly – all warning signs of sepsis, a life-threatening condition if not treated with IV antibiotics within an hour.

It wasn’t until 16 hours later, however, that she was given IV antibiotics.

However, it was too late. Despite the efforts of multiple doctors, she was pronounced dead at 8:52 a.m.

A postmortem examination found signs of septic shock and peritonitis, though the exact source of the infection could not be determined.

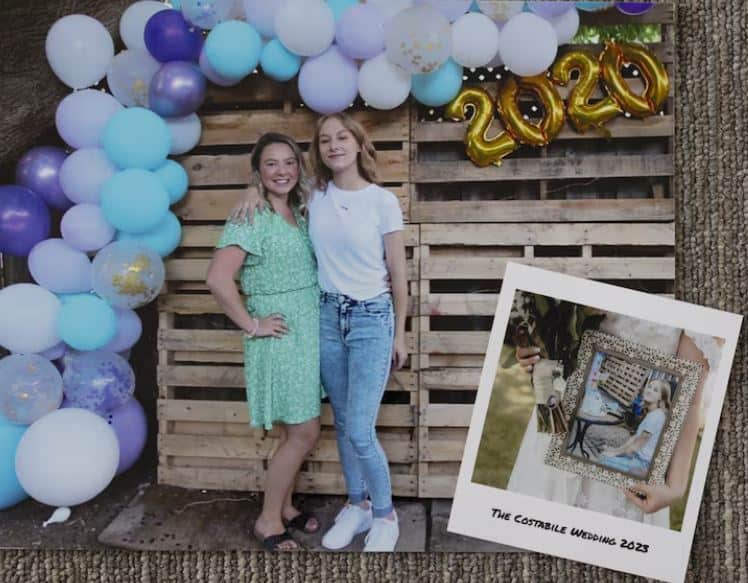

After examining her sister’s medical records, her sister, Kassandra Costabile filed a formal complaint with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario.

Danny Kastner, a lawyer who represents eight female doctors who had previously complained about Dr. Duic, argued that stronger disciplinary action could have prevented her death.

Laderoute’s family believes the system failed her.

Her sister hopes that by raising awareness of what happened, they will be able to prevent others from suffering the same fate.